A Modest Proposal

Agroforestry, plant-based materials, and rethinking design education with Christine Facella

Keeping global warming below 1.5 °C to avoid dangerous climate change1 requires the removal of vast amounts of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, as well as drastic cuts in emissions. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) suggests that around 730 billion tonnes of CO2 (730 petagrams of CO2, or 199 petagrams of carbon, Pg C) must be taken out of the atmosphere by the end of this century2. That is equivalent to all the CO2 emitted by the United States, the United Kingdom, Germany and China since the Industrial Revolution. No one knows how to capture so much CO2.

Forests must play a part. Locking up carbon in ecosystems is proven, safe and often affordable3. Increasing tree cover has other benefits, from protecting biodiversity to managing water and creating jobs.

-“Restoring natural forests is the best way to remove atmospheric carbon,” Nature, April 2019

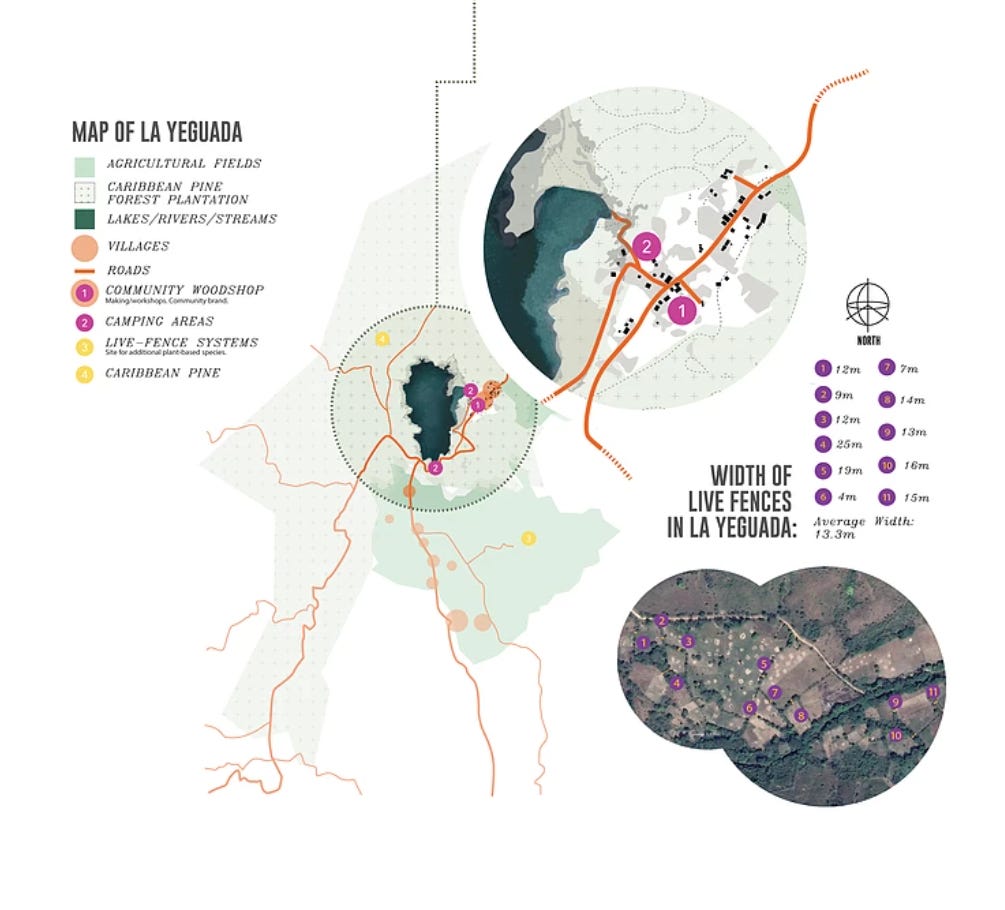

In the 1960’s, 7090 hectares of degraded land (former cattle ranches) in La Yeguada, Central Panama, was reforested to protect the country’s first public hydroelectric plant. Caribbean pine (Pinus caribaea) was planted as it was the only species that survived and thrived in the degraded soils. Besides protecting soils from eroding into the watershed, the pine plantation offers the surrounding communities livelihoods: 2000 hectares can be rotationally harvested and used by surrounding communities, who currently fabricate shipping pallets.

Caribbean pine in La Yeguada (Credit: Fundacion CoMunidad)

Today, if La Yeguada’s soil had not been first stripped of its richness by ranching and then reforested in monoculture with the exotic Caribbean pine, the natural vegetation would be premontane wet forest, a forest ecosystem characterized by a combination of mountainous and tropical elements, with slightly less precipitation than a rainforest. It would be home to many kinds of mosses, lichens, ferns, and orchids, supporting a diverse array of mammals, birds, and amphibians, sequestering carbon at a rate unmatched by almost any managed landscape.

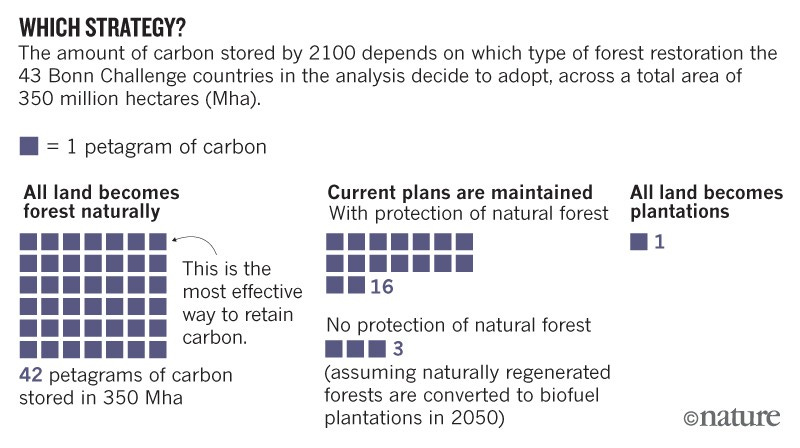

The Caribbean pine was a half-measure of repair, planted as an ecological barrier against erosion and further degradation of land already degraded by agriculture. Forest plantations made up 5% of the world’s forested area in 2016; that percentage, if countries follow their current plans and commitments, will increase in the coming decades. Under the Bonn Challenge and other initiatives, 43 countries across the tropics and subtropics (where trees grow quickly, sequester more carbon, and don’t interfere with the earth-cooling reflection of solar energy off snow that happens at high latitudes) have pledged to restore forests to nearly 300 million hectares of eligible land. That’s a promising commitment. But the details are critical.

Restoration plans published by about half of the countries participating, covering two-thirds of the total pledged area, give a view of the range of strategies countries are choosing to achieve reforestation goals. An article in Nature outlines the possibilities and the outcomes. Simplified, there are three main paths for any piece of land:

First, degraded and abandoned agricultural land will be left to return to natural forest on its own. Second, marginal agricultural lands are to be converted into plantations of valuable trees, such as Eucalyptus for paper or Hevea braziliensis for rubber. Third is agroforestry, which involves growing crops and useful trees together.

The aim of the Bonn Challenge, launched by the German government in 2011, is to act on the IPCC recommendation that “boosting the total area of the world’s forests, woodlands and woody Savannah’s could store around one-quarter of the atmospheric carbon necessary to limit global warming to 1.5 °C above pre-industrial levels.” A closer look at the plans countries have for foresting suggests that their current pathways will have nowhere near the necessary or presumed level of impact. Why? 45% of the commitments—almost half—involve planting vast monocultures of trees to be harvested periodically for profit, rather than introducing diverse, multispecies systems that could support wildlife, serve as stable sites for long-term carbon sequestration, or offer more than a single product to local harvesters and craftspeople. In some cases, forest plantations reduce pressure on natural forests by providing an alternative source of wood. But in other cases, forest plantations replace natural forest. And they aren’t as good.

The Nature article, tellingly titled “Restoring natural forests is the best way to remove atmospheric carbon,” explains that

Although [forest plantations] can support local economies, plantations are much poorer at storing carbon than are natural forests, which develop with little or no disturbance from humans. The regular harvesting and clearing of plantations releases stored CO2 back into the atmosphere every 10–20 years. By contrast, natural forests continue to sequester carbon for many decades.

The type of forest restoration that takes place in countries participating in the Bonn Challenge will determine the amount of carbon sequestered (Credit: S.L. Lewis et. al. via Nature)

Countries have chosen and will continue to choose plantation forestry for the money it brings in. In Central America, huge swaths of forest have been destroyed in the conversion to cattle ranch land, leading to soil degradation, greenhouse gas emissions and reduced carbon sequestration, and a general depletion of ecosystem services. The massive ecological destruction carried out through settlement patterns over the last century is inseparable from and intensified by the displacement of indigenous people from their ancestral lands. Some governments and organizations have responded to deforestation, piecemeal, by working with farmers to reforest ranches and turn them into timber plantations.

The timber plantations do offer some economic and ecological benefits. They’re certainly better, carbon-wise, than ranches, and some of the organizations aiding in getting them planted also support the local workforce in developing skills in timber processing and furniture making to create alternatives to the ranching. Most of the plantations, however, are monocultures of pine or non-native teak. They capture and store only a fraction of the carbon the original tropical moist forest or premontane wet forest would. They don’t offer the shelter and food to wild animals a natural forest would, nor do they necessarily provide a diversity of opportunities for different kinds of work, creativity, or preservation and evolution of a community’s craft cultures.

Stacked timber from the La Yeguada Caribbean pine plantation (Credit: Fundacion CoMunidad)

Species selection for plantations is driven by market demand, among other factors (things like the rate at which a species grows, or how well it can adapt to degraded soils, also weigh in). Designers, who exercise discretion over their choice of materials and influence the broader demand for certain kinds of wood, make up a strong constituency of the market. They’re often unaware of the impact their choices have on the landscapes of countries they may never see, and may not look too closely into the ecological origins of their options. There are unasked questions and unheeded nuances, places of ambiguity or ignorance, related to the origins of materials in geographically distant systems of agriculture and labor.

My curiosity about the places along product supply chains where connection and context are lost, and how they might be restored, led me to connect with Christine Facella. Christine is a product designer and landscape architect whose work, through the service-based and educational design group called Modest she founded, aims to bring clarity and resources to these spots of need.

Modest works to strengthen maker communities and give designers information and strategies they can use to support biodiversity and restore forest ecosystems through the choices and connections they make. At the invitation of the Community Association of La Yeguada, Modest partnered with the Panama-based Fundacion CoMunidad, students at Parsons School of Design, and a team of science and design consultants to find ways to shift activities and processes in La Yeguada pine plantation and community woodshop toward a more sustainable model.

They identified uses for waste, like sawdust and cutoffs, and began exploring the possibilities for the cultivation of a multitude of other plants to be grown in tandem with the managed forests or in live fences around agricultural fields (an example of agroforestry). In the future, these newly incorporated plants could be used for finishes or fibers to support or expand the existing product lines of local makers. A timber plantation reforested with a robust multiplicity of species, capable of supporting wildlife and improving soil health while also making new plant-based materials available (dyes, finishes, fibers, and more), would offer far more to the human and other-than-human communities surrounding it.

From the site analysis of the La Yeguada (Credit: Modest)

To support the utilization of a richer variety of plant-based materials, Modest has led students at Parsons School of Design in researching plant-based materials from species native to Central America. The plant-based materials library is open-access, and building on it, Facella is now looking deeper in the variety of applications of plant-based materials. Looking for plant dyes that might be used to stain wood, for example, or identifying the plant oils best suited as finishes.

A sample from Modest’s plant-based materials library highlights uses for pokeweed (Credit: Modest)

Modest also organizes skill-building workshops and maker-to-maker exchanges in service of communities they partner with. Based on the kind of support a community requests, they might provide entrepreneurial support (helping set up logistical or administrative infrastructure for a small business, helping with branding, or finding funding), or connect workers in one place with others who can teach a specific skill or technique, like wood joinery, mold-making, or creating a cast-able compound from sawdust. In Panama, partners in the rural La Yeguada community asked for help brainstorming and testing ideas for using scrap wood discarded from timber processing. In Haiti, the organization Partner for People and Place asked for help making packaging made from plastic waste for their locally made plant-based soaps and shampoos. The new packaging will replace the imported packaging products they currently use, grounding more of the process locally. Modest is named what it is for this emphasis on the local, and for its dedication to supporting small-scale production, local and regional economies in healthy relationship with local and regional ecologies, and modestly scaled, thoughtful responses to specific needs.

The La Yeguada community wood shop (Credit: Fundacion CoMunidad)

The relationship between the landscape and the objects made from its products is visible, tangible both before and after the objects exist in usable forms. A forested skyline is one obvious view of the former stage. What represents the latter? It could be soil, or it could be toxic synthetic waste. Christine Facella explains: “The ‘ingredients’ to our products become biological nutrients, so in a way we continue to design landscapes at the end of the product’s life.” Take, for example, the afterlife of a product made of wood. Wood contains high amounts of lignin, which bacteria and fungi break down. Depending on what’s done with it, the wood a product is made from could return nutrients to the soil, or feed into another product, serving another purpose: “the wood, chipped up, could become the substrate of mycelium which could be used to create a different product, such as packaging.” Or the breakdown of wood in a natural or agricultural setting could add organic matter to the soil—“a much different scenario,” Facella says, “than what is happening in historic, even current landfills filled with toxic synthetic materials.”

How do you teach students and designers to see themselves not solely as creators of products, but also as co-creators of landscapes, economies, and ecological realities?

Facella encourages her students at Parsons, where she teaches product design, to look to other disciplines for perspective and inspiration. Authors like Robin Wall Kimmerer and John McPhee and readings exploring ecology, materials, plants, and human-nature relationships serve as conduits to more expansive ways of thinking about design, and she often chooses them over the expected design readings.

She guides students in plant research to help them develop an understanding of the living sources of materials they can work with, and their ecological functions and faunal relationships. She spends a lot of time drawing diagrams to illustrate points and systems simply, and leading students in mapping exercises to make sure they’re examining ecological and social systems at multiple scales for a fuller picture.

All this because she hopes, she says, that “through the magic of stories, through research at multiple scales, through field trips and diagramming and later on designing,” students and designers will gain a fuller understanding of the ways in which their work relates to regional geographies, ecosystems, and communities. By dismantling some disciplinary walls, and working in partnership rather than in sequence with the people and places providing materials, designers gain a fuller understanding of the systems they are part of. With this fuller understanding should come a fuller, more inclusive, more responsible, and more honest concept of the purpose and uses of design.

Modest’s projects, Facella is clear, do not address deforestation at the massive scale at which it’s happening in the global tropics—this, she says, is something we have to do as a global human community, transforming the patterns in our lives and economies to decrease consumption, and reframing our relationship to our non-human community. Rather, consider Modest’s work a set of proposals, highlighting one opportunity to right some of the wrong in a specific geographic region. And doing this through the cultivation of managed forests and the making of usable goods, both activities, in Facella’s words, “integral to the human story.”

Buildingshed is on Instagram.

https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-019-01026-8#ref-CR1

https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-019-01026-8#ref-CR2

https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-019-01026-8#ref-CR3